This profile was originally published on Research Matters

Is history just a list with a story?

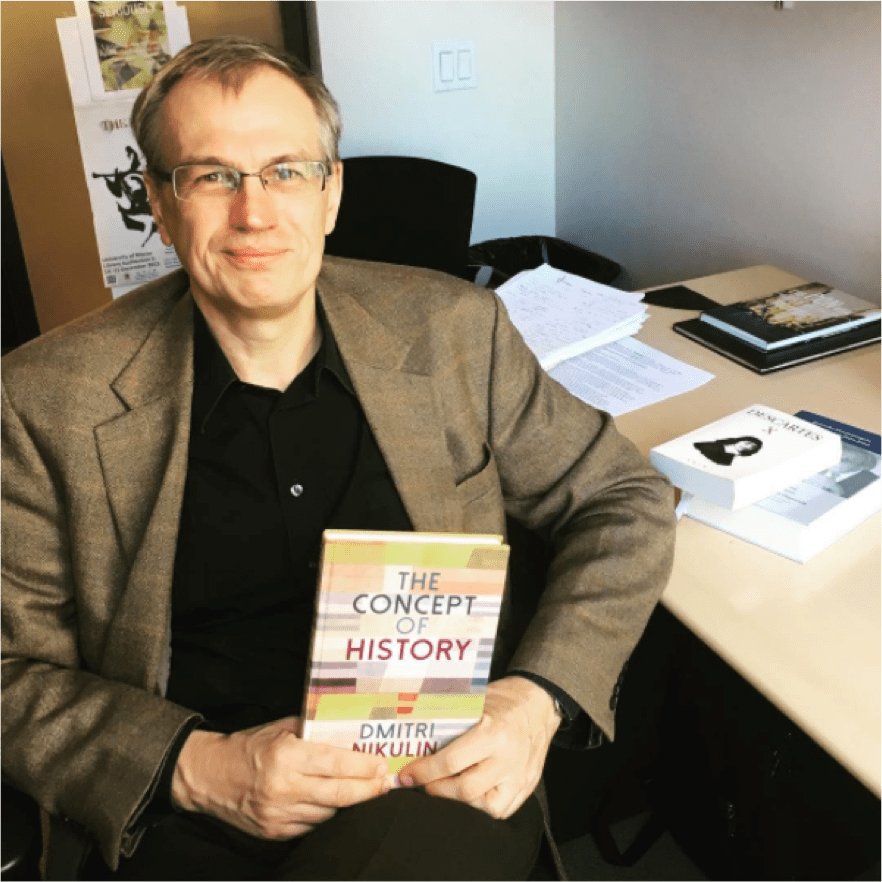

This question underlies New School for Social Research Philosophy Professor Dmitri Nikulin's latest book, The Concept of History (Bloomsbury). Nikulin, who will serve as Chair of the Department in 2017-18, asks what we even mean when we use the word history, returning to the discipline's origins in Ancient Greece. He suggests that to get the clearest picture of what history meant to the ancients, we should push past even Herodotus, typically considered “the father of history.” Instead, we should look to Hecataeus and Hellanicus. The surviving 400 fragments of their work provide a key insight that has less to do with the truth of history than with the way our concept of history has evolved.

To get away from the common modern conception of history as universal and unilinear, Nikulin examines how these earliest historians conceived of their craft. “When I looked at the way in which people were narrating history at that time,” he said, “I started to realize that they looked at history very differently because they didn't yet have the idea of a final destination for humankind.”

Without this clear destination in mind, history looks like an amalgam of genealogies and geographies; and instead of a single and all-encompassing version of history, we find thinkers narrating diverse simultaneous histories. They are the parallel stories of different peoples populating different places, told from multiple perspectives. Each of these perspectives is embodied by any single person: we all inhabit different streams of overlapping histories (individual, professional, familial, etc.).

“I take it that we inhabit multiple histories, not just one,” Nikulin said, describing one conclusion to take from this perspective. The absence of an overarching narrative among the early Greek historians challenges two touchstones of modern historical thought: the idea of an origin and that of a final end. It underscores the fact that these multiplicities only come together in a single overarching plot-history as a unified narrative-much later.

This perspective required Nikulin to come up with an alternative reading of how the concept history came into being.

In his view, history has always been partly a project of keeping records of details and minutiae like names, events, things, battles, and places. “By doing so, we bring in some order, [and] arrange details in many different ways,” Nikulin said. He emphasized the decision to avoid using the word facts, instead opting for the word details. In this, Nikulin is acknowledging that facts often come laden with narrative. For Nikulin, “The fabula of history,” that is, the story and the narrative that the list tells, “really refers to the narrated plot of what happened, which ties all these details together.” In other words, the combination of details and fabula becomes the real stuff of history.

Though Nikulin insists that the arrangements of any set of details and fabulae remain multiple, this combination of two ingredients-details and the narrative that stitches them together-produces the more familiar picture of history, which intends in part to preserve something like living memories. Such memories are crucial for what it means to be human. “I take it that our historical being consists in our having a place in a history […] in inhabiting a history. And we do that by being included in a narrative.” Like Hannah Arendt, Nikulin argues that a purpose of history is to save us from “the futility of oblivion.”

In the ancient genre of catalogue poetry, for example, we often see extraordinary efforts to preserve meticulously detailed lists and accounts of people and events. These efforts arise from the notion that the practice of history constitutes a preservationist act. According to

Nikulin, this idea pervades ancient histories. “You can find it all over the place from the Bible to Hecataeus to Hesiod,” he said, “It's all about the genealogies of humans and of the gods.” Genealogies give both an order to history and a place to humans, who are either part of the history or involved in its transmission and significance. “If you want to save a people from the futility of oblivion,” he explained, “genealogy is important.”

At the same time, this conception of the purpose of genealogy and its relationship to the historical gives Nikulin space to think about the relationship of history to poetry in the ancient world. “We moderns have a very Romantic understanding of the figure of the poet,” he said, referring to the intellectual movement spanning the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, “according to which the poet is essentially a maniac […] He is inebriated, enthusiastic, and he empties himself in order to let something else, perhaps divinity, speak through him.” But when thinking more carefully about the figure of a poet like Homer, Nikulin argued, “[the poet] is not a maniac.” Rather, he carries out the sober task of preservation and transmission of knowledge. In this sense, Nikulin suggested, “History is probably the first prosaic genre,” which is to say, history was the first non-poetic genre.

This wedding between narrative and genealogy, argues Nikulin, marks a decisive moment in the evolution of history. History begins to look more familiar precisely when the catalogue or list joins with a fabula or narrative. These narratives are malleable, changing over the course of generations, and opening history itself to constant reinterpretation-even as history remains somewhat fixed by the events that the narratives build into a plot. In The Concept of History, Nikulin charts a judicious middle ground between seeing history as a closed, unified and unidirectional march, and seeing it as a jumble of infinitely competing narratives.

How might this influence the practice of history and our understanding of its relationship to other fields?

Nikulin points out that others have suggested that historians can only use the literary genres (comedy, tragedy, detailed lists, etc.) available in their own moment to interpret events. But he emphasizes the inventive possibilities of historical narrative. “We can use certain conventions, but we can invent many other interesting ways of reading histories,” he said. With recent critical understandings of gender, for instance, we might be able to construct novel historical narratives that might have been difficult to conceive up to now. This has significant implications for our understanding of politics as well, given the intimate inscription of the historical. Given the understanding of history as multiple and revisable, politics becomes equally subject to such reconsiderations.

In The Concept of History, Nikulin does not limit his claims to ancient histories, but there is significant value in learning what historians intended before more familiar contemporary conceptions of historical work hardened into tradition. Nikulin's book opens up conversation about what history can aspire to be, precisely by learning about how the discipline came to be constituted as being invented.